Across everyday life, the menu of options has expanded far beyond what most of us can easily process.

- In the United States alone, roughly 30,000 new consumer products enter the market each year — a single superstore may stock up to 140,000 distinct items at any given time.

- Medicare beneficiaries in many counties must sort through 40–60 health plan options, with some markets offering more than 80.

- High-school graduates face more than 4,000 accredited colleges, each with hundreds of programs to consider.

- In elections, many democracies now present five or more viable parties on the ballot where once there were only two.

The promise behind this abundance is straightforward—more options should make it easier for people to find a good fit— right? Not necessarily.

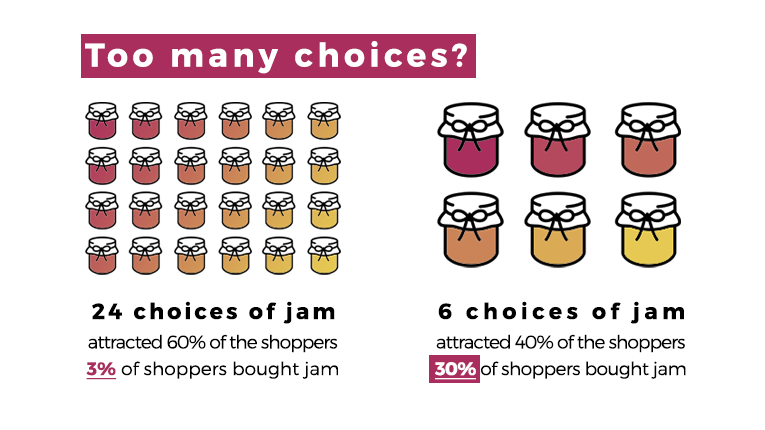

The first clear evidence that “more” can sometimes mean “less” in practice came from a set of studies by Professors Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper in 2000. In a field experiment at Draeger’s Supermarket in Menlo Park, California, shoppers encountered a tasting booth that offered either 24 flavors of jam or 6. Here's what they found:

- The larger display drew more people—about 60% stopped when 24 flavors were present, compared with about 40% when there were 6.

- But the smaller display helped people decide: nearly 30% of those who saw 6 options purchased a jar, while only about 3% of those who saw 24 did so.

This asymmetry—initial attraction to variety paired with difficulty choosing—came to be known as “choice overload” and offered some of the first empirical evidence that very large assortments can have adverse consequences for selection and action.

If the expansion of choice is here to stay, the task is not to wish it away but to build a practical science that helps people meet it. At the Choice Architecture Lab at Columbia Business School, not only do we research choice overload and its effects, but also how we can work toward a framework that equips people to identify what is relevant, to compare and contrast alternative options, and to choose in line with their goals — so that abundance becomes enabling rather than paralyzing.

Yet even with this expansion, how is it that we still experience moments when, despite all the available options, the one we want is missing? Maybe it's a college major that lives at the intersection of fields, a job that blends responsibilities rarely housed under a single title, or a product or policy that would serve needs not yet recognized. For this reason, a second strand of our work focuses on creating choices—on the processes by which individuals and organizations generate, evaluate, and choose new options. “To invent is to discern, to choose,” wrote Henri Poincaré.

Guiding this generative side is Professor Sheena Iyengar’s Think Bigger methodology, a six-step guide to moving from ill-defined problems to well-formed possibilities. We study how people ideate best, how ideation should be evaluated, and how emerging tools—especially generative AI—are changing the way ideas are produced and curated. The aim is to widen the set of possibilities while keeping human judgment at the very center.